By Dave DeWitt

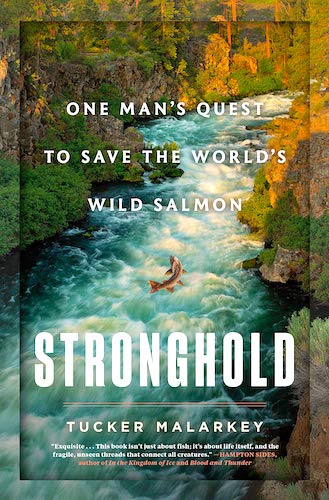

Guido Rahr with his 83-pound taimen. Photo by Matt Sloat, courtesy of Spiegel & Grau,

In 2018, salmon expert Guido Rahr was trying his hand at trout fishing on the Tugur River in Kamchatka, Russia. He was attempting to catch a Siberian taimen, an obscure trout species, on a fly, which had never been done before. Why not? Well, first, because fly fishing was virtually unknown in Russia, and second, because the rivers these fish live in are so remote that they make the term “wilderness” look like Central Park. The only Russians who fished these rivers were super-wealthy oligarchs like Alexander Abramov, chairman of steel company Evraz, whose net worth was more than seven billion U.S. dollars. Guido was a guest of Abramov’s and was staying at his fishing lodge on a tributary of the Tugur River. “Guido had penetrated the highly selective fraternity of Russia’s fishing elite,” writes Tucker Malarkey, author of Stronghold, “and it was an intimate group.” And that group was full of Putin’s buddies and was trying to promote the Russian Salmon Partnership that would be using its oligarchical skills to keep these rivers pristine forever. If any of the salmon–or the closely related taimen trout–could be taken with flies, that mystique would not only help the cause, but also keep industries such as logging from ruining the watersheds that were the prime salmon and trout fishing habitats.

After days of getting skunked by the finicky taimens that were ignoring all the flies flung at them by Guido and the other fly fishing experts from around the world, Guido decided to make a “superfly” that he thought would tempt the taimen. It was a “tube fly about eight inches long with weighted eyes and a head made of spun elk hair,” Malarkey writes. “It had a long brown wing and a bit of flash in it. On the end was a stinger hook, a single hook attached to a loop of monofilament line that hung toward the end of the wing. Guido had started attaching these hooks, with the reasoning that no matter how tentatively the fish grabbed the fly with its mouth, it would end up with the hook.” The next day, Guido hooked and landed one of the first taimens taken by fly fishing. It weighed 43 pounds. Did I forget to mention that taimens grow to be huge? Guido’s second taimen was much larger–83 pounds!

It turns out that taimens are the largest of all the Salmonids, easily beating lake trout, the heaviest of which was 72 pounds. The world record for taimens on a fly is 107 pounds, and that fish exceeded six feet in length. The largest reliably recorded specimen, caught in Russia’s Kotui River in 1943, measured an astonishing 83 inches long and weighed 231 pounds.

The subtitle of Stronghold is “One Man’s Quest to Save the World’s Wild Salmon,” and the man Tucker Malarkey is referring to is, of course, Guido Rahr. This is a fascinating book and I highly recommend it it for fishermen, seafood lovers, and those people who support sustainable fishing practices. Many people will ask, “So, what’s the big deal about wild trout and salmon? Hatcheries can produce all the trout and salmon needed.” Yes, but those hatchery fish are not wild. I don’t have the space here to discuss all the problems associated with hatchery-produced salmon and trout–Tucker Malarkey does an excellent job with that in Stronghold. But I will present just one example. When hatchery salmon are released in many of the streams of a watershed, they move out to the ocean where they live for years until maturity. When they come back to fresh water to spawn and die, do they return to the streams where they were released? No, they return to the location of the hatchery. That fact strikes me as a bit sad.